Mastering Cash Flow in Construction: Overcoming Challenges to Ensure Financial Stability

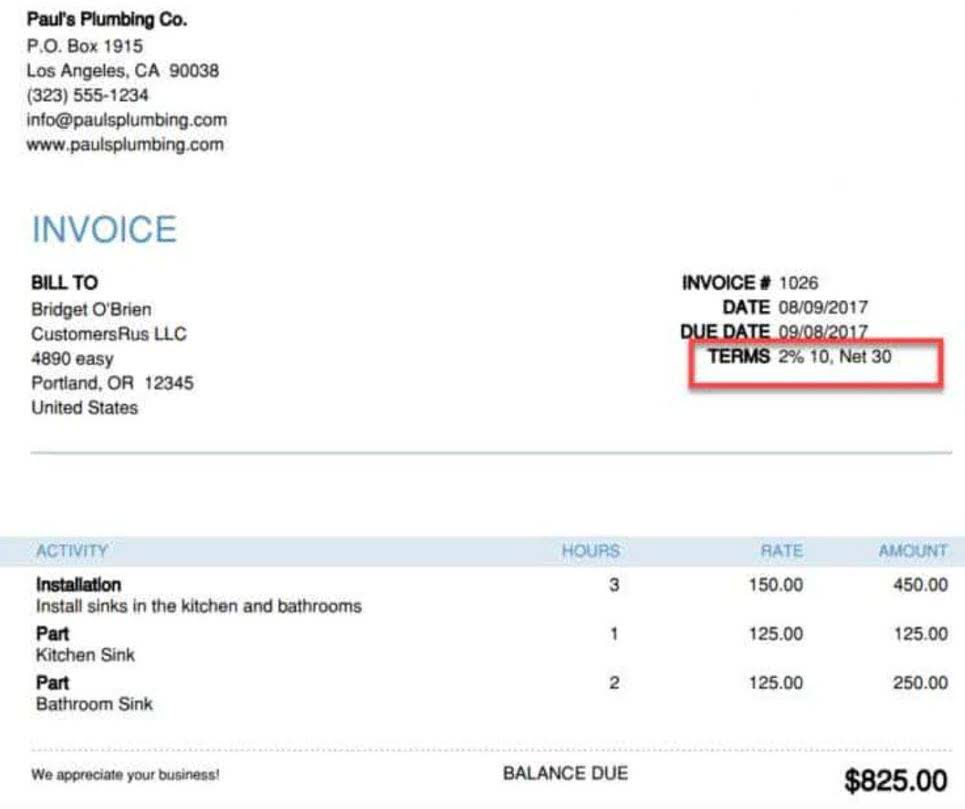

If you wait until the end of the job to bill, you won’t have the cash to cover the extra costs as they occur. You can also offer discounts for early payment to encourage your customers to pay quickly. However, don’t make the discount so steep that it negatively affects you if your customers choose to use it.

Recent Govt. Jobs

Buildertrend financial tools like the Budget and QuickBooks integration help teams achieve this. We know many residential builders are small family-owned businesses – every penny counts. Consider putting new payment policies in place and work them into your contract so the payment terms are clearly defined and everyone knows what to expect. These types of offers can also help you win over potential leads and grow your business. This can help measure if you’re able to cover your bills and keep your business moving forward.

How to Get Your North Carolina General Contractors License in 2024

- Key performance indicators (KPIs) measure how well a business is doing compared to its objectives.

- This figure is the foundation upon which all cash flow projections are based.

- You can do this by sending invoices immediately, offering payment incentives, writing clear terms, checking credit reports before making any deals, and restructuring terms with non-payers.

- These curves help in mapping out how the remaining budget will be spent over time, based on the project’s phases and milestones.

- Without this type of analysis, your business could be floating along with no way to tell where it is heading or if there is a giant reef coming up.

Cash flow in construction refers to the movement of funds into and out of a construction project over a specific period. It’s the lifeblood of any construction project, determining its financial health and operational viability. Essentially, it tracks the cash https://www.bookstime.com/ that flows in from clients and financing sources against the cash that flows out for project expenses like labor, materials subcontractor payments and equipment costs. Where your construction company’s money comes from, and where it goes is called cash flow.

What Is a Work in Progress Schedule? Construction Accounting

A positive cash flow means that a construction project is receiving more money than it is spending, which is essential for keeping a project moving forward without interruption. This status allows a construction firm to cover its bills on time, invest in necessary resources and even save for future projects. Over 61% of construction companies say that collecting retainage is “very important” or “the most important factor” in managing cash flow. But because retention payments are often withheld until project completion, collection delays commonly exceed those of regular payments.

Offer payment options or discounts for early payment

With improved operations, your construction company can leverage budget allocations, hit deadlines, ensure profitability and keep customers happy. All of these factors are vital to the long-term success (and financial wellbeing) of your construction business. If you’re constantly using incoming client payments to fulfill the next bill, you’re not going to see any long-term profitability.

How to make a cash flow projection

You need to be able to quickly identify how each project on your books affected your cash position overall. Apply various curves (such as bell curve, linear, front-loaded, or back-loaded) to the schedule of values based on the scope of work. These curves help in mapping out how the remaining budget will be spent over time, based on the project’s phases and milestones. Procore is committed to advancing the construction industry by improving the lives of people working in construction, driving technology innovation, and building a global community of groundbreakers. Our connected global construction platform unites all stakeholders on a project with unlimited access to support and a business model designed for the construction industry.

- About 85% of cash in construction comes from project work in progress, which means cash flow performance depends on the project manager’s cash flow management.

- It makes it easier to review and manage cash reserves on an ongoing basis.

- By regularly updating and reviewing these projections, companies can anticipate potential shortfalls or surpluses and adjust their strategies accordingly.

- Gross profit margin and net profit margin are important KPIs for every construction company.

- Construction companies invested in more technology, software, and digital solutions over the past year, with many office staff adopting tools to support remote work for office staff.

- To navigate this, it’s essential for construction business owners and their leadership teams to understand and apply the basics of cash flow management.

- Every construction company needs the right accounting reports and financial statements to identify where their cash flow is healthy, and where it needs support.

Cash flow projection for contractors: Predicting the future

This approach ensures comprehensive financial management, catering to both micro and macro-level needs. In this article, we dive into the intricacies of cash flow within the construction sector, how to create a cash flow projection report and industry best practices around forecasting cash flow. There are great systems available for construction companies today which dramatically improve their ability to manage information and track what’s happening. This might be accounting tools, project forecasting tools, scheduling tools or project delivery tools. Most companies find it relatively to create projections at the beginning of a project, because there aren’t many moving parts. But once a project begins and people start performing work, it’s easy for your construction cash flows to change and get out of control quickly.

The Significance of Training in Cashflow Management

As the payment delay extended, the painting subcontractor found themselves unable to pay their workers. Without the necessary compensation for their time, the painters stopped coming to work, halting progress on the project. This standstill not only affected the immediate job but also the contractor’s reputation and ability to secure future work. Eventually, the lack of cash flow, compounded by the inability to complete work and generate income, led to the business’s downfall. This stark example illustrates the domino effect that can result from over-reliance on a single source of income, especially in an industry where cash flow is the engine of daily operations. To get an accurate picture of contractor cash flow, first identify and track the timing of when cash is entering your business versus when it’s going out.

- Implementing an integrated construction project management software enhances the efficiency and accuracy of cash flow projection reports.

- A construction business with negative working capital needs to get its hands on cash as soon as possible.

- A cash flow forecast helps predict future cash issues, so you can take action before it impacts your bottom line.

- A positive cash flow means that a construction project is receiving more money than it is spending, which is essential for keeping a project moving forward without interruption.

- If you are a customer with a question about a product please visit our Help Centre where we answer customer queries about our products.

What is a cash flow forecast?

Posted: January 31, 2022 10:20 am

According to Agung Rai

“The concept of taksu is important to the Balinese, in fact to any artist. I do not think one can simply plan to paint a beautiful painting, a perfect painting.”

The issue of taksu is also one of honesty, for the artist and the viewer. An artist will follow his heart or instinct, and will not care what other people think. A painting that has a magic does not need to be elaborated upon, the painting alone speaks.

A work of art that is difficult to describe in words has to be seen with the eyes and a heart that is open and not influenced by the name of the painter. In this honesty, there is a purity in the connection between the viewer and the viewed.

As a through discussion of Balinese and Indonesian arts is beyond the scope of this catalogue, the reader is referred to the books listed in the bibliography. The following descriptions of painters styles are intended as a brief introduction to the paintings in the catalogue, which were selected using several criteria. Each is what Agung Rai considers to be an exceptional work by a particular artist, is a singular example of a given period, school or style, and contributes to a broader understanding of the development of Balinese and Indonesian paintng. The Pita Maha artist society was established in 1936 by Cokorda Gde Agung Sukawati, a royal patron of the arts in Ubud, and two European artists, the Dutch painter Rudolf Bonnet, and Walter Spies, a German. The society’s stated purpose was to support artists and craftsmen work in various media and style, who were encouraged to experiment with Western materials and theories of anatomy, and perspective.

The society sought to ensure high quality works from its members, and exhibitions of the finest works were held in Indonesia and abroad. The society ceased to be active after the onset of World War II. Paintings by several Pita Maha members are included in the catalogue, among them; Ida Bagus Made noted especially for his paintings of Balinese religious and mystical themes; and Anak Agung Gde Raka Turas, whose underwater seascapes have been an inspiration for many younger painters.

Painters from the village of Batuan, south of Ubud, have been known since the 1930s for their dense, immensely detailed paintings of Balinese ceremonies, daily life, and increasingly, “modern” Bali. In the past the artists used tempera paints; since the introduction of Western artists materials, watercolors and acrylics have become popular. The paintings are produced by applying many thin layers of paint to a shaded ink drawing. The palette tends to be dark, and the composition crowded, with innumerable details and a somewhat flattened perspective. Batuan painters represented in the catalogue are Ida Bagus Widja, whose paintings of Balinese scenes encompass the sacred as well as the mundane; and I Wayan Bendi whose paintings of the collision of Balinese and Western cultures abound in entertaining, sharply observed vignettes.

In the early 1960s,Arie Smit, a Dutch-born painter, began inviting he children of Penestanan, Ubud, to come and experiment with bright oil paints in his Ubud studio. The eventually developed the Young Artists style, distinguished by the used of brilliant colors, a graphic quality in which shadow and perspective play little part, and focus on scenes and activities from every day life in Bali. I Ketut Tagen is the only Young Artist in the catalogue; he explores new ways of rendering scenes of Balinese life while remaining grounded in the Young Artists strong sense of color and design.

The painters called “academic artists” from Bali and other parts of Indonesia are, in fact, a diverse group almost all of whom share the experience of having received training at Indonesian or foreign institutes of fine arts. A number of artists who come of age before Indonesian independence was declared in 1945 never had formal instruction at art academies, but studied painting on their own. Many of them eventually become instructors at Indonesian institutions. A number of younger academic artists in the catalogue studied with the older painters whose work appears here as well. In Bali the role of the art academy is relatively minor, while in Java academic paintings is more highly developed than any indigenous or traditional styles. The academic painters have mastered Western techniques, and have studied the different modern art movements in the West; their works is often influenced by surrealism, pointillism, cubism, or abstract expressionism. Painters in Indonesia are trying to establish a clear nation of what “modern Indonesian art” is, and turn to Indonesian cultural themes for subject matter. The range of styles is extensive Among the artists are Affandi, a West Javanese whose expressionistic renderings of Balinese scenes are internationally known; Dullah, a Central Javanese recognized for his realist paintings; Nyoman Gunarsa, a Balinese who creates distinctively Balinese expressionist paintings with traditional shadow puppet motifs; Made Wianta, whose abstract pointillism sets him apart from other Indonesian painters.

Since the late 1920s, Bali has attracted Western artists as short and long term residents. Most were formally trained at European academies, and their paintings reflect many Western artistic traditions. Some of these artists have played instrumental roles in the development of Balinese painting over the years, through their support and encouragement of local artist. The contributions of Rudolf Bonnet and Arie Smit have already been mentioned. Among other European artists whose particular visions of Bali continue to be admired are Willem Gerrad Hofker, whose paintings of Balinese in traditional dress are skillfully rendered studies of drapery, light and shadow; Carel Lodewijk Dake, Jr., whose moody paintings of temples capture the atmosphere of Balinese sacred spaces; and Adrien Jean Le Mayeur, known for his languid portraits of Balinese women.

Agung Rai feels that

Art is very private matter. It depends on what is displayed, and the spiritual connection between the work and the person looking at it. People have their own opinions, they may or may not agree with my perceptions.

He would like to encourage visitors to learn about Balinese and Indonesian art, ant to allow themselves to establish the “purity in the connection” that he describes. He hopes that his collection will de considered a resource to be actively studied, rather than simply passively appreciated, and that it will be enjoyed by artists, scholars, visitors, students, and schoolchildren from Indonesia as well as from abroad.

Abby C. Ruddick, Phd

“SELECTED PAINTINGS FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE AGUNG RAI FINE ART GALLERY”